The ancient, walled city of Tehran appealed to many nineteenth-century adventurers—including those who rode around world on bicycles. Around 1885, during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah, Tehranis first saw bicycles, known as “iron horses,” in the hands of tourists and foreign embassy staff in the alleys and markets. Since then, the phenomenon of cycling in Tehran has experienced ups and downs along with the political, social, and physical changes in the city. Through an analytical study of history that sheds light on the way forward, the Cycling in Tehran project aims to strengthen the position of cycling in the transportation system of Tehran and then in other metropolises, especially in Muslim, Middle Eastern, and developing countries.

For about a century and a half, waves of modernity, as an external force from the West, have continuously influenced Iranian society, and in some cases even used the opportunity for a process of adaptation and coexistence within Iranian society and Iranian cities. As a result of this often one-sided interaction, some scholars have argued that a sense of incomplete modernism or an Iranian version of modernism has emerged. The evolutionary history of the bicycle in Iranian society and Iranian cities, including Tehran, is not excluded from this trend.

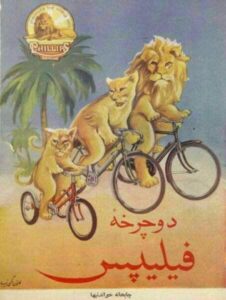

In the beginning, bicycles were mainly used by the elite, such as embassy staff, the royal family, and the upper classes, mostly for recreation and entertainment. Gradually, bicycles became popular among the middle class and workers for commuting, shopping, and transporting goods. In 1910, taxes were imposed on bicycles, and by 1926, the number of cyclists in Tehran had increased significantly, leading to the introduction of regulations and mandatory bicycle registration for disciplinary purposes.

During the first Pahlavi era, the destruction of the old city center and the construction of straight roads paved the way for an automobile-centric city. The few expensive imported cars did not pose much competition for bicycles at first. The 1950s can be considered as the peak of cycling in Tehran. However, Iran’s changing position in the global dynamics and the deeper level of modernization during the second Pahlavi era changed the situation. In the 1960s, the city of Tehran suburbanized rapidly due to a surge in immigration, increased imports of cars and motorcycles, the growth of the middle class, rising oil revenues, and the availability of cheap fossil fuels.

Industrial plans, including automobile factories and government support, shifted political attention from bicycles and pedestrians to motorcycles, cars, and speed. Cycling was culturally marginalized, transformed from a vehicle of high status to one of low status, considered only for those without a driver’s license. This trend continued after the Islamic Revolution.

Despite small-scale cycling projects since the 1990s, a car-centric mindset among the public and officials, coupled with factors like the hilliness of the suburban areas, social resistance to women cycling, and the lack of a cycling network, led to the failure of the projects. In 2018, with the support of the former mayor, cycling gained momentum. The international sanctions, the shift in municipal priorities, and countermeasures in parallel with efforts to promote cycling hindered its flourishing.

Currently, the cycling culture in Tehran is experiencing stagnation but remains vibrant in need of recognition in urban planning. Transforming Tehran’s car-centric design into a human-centered, health-oriented model is a gradual process. Small, consistent actions, especially in central areas, can contribute to this transformative direction.

In 2018, for the first time, with the direct support of the previous mayor, cycling gained momentum in the city and efforts were made to transform it into a social movement. Shifts in government priorities, external sanctions, and neutralizing measures taken alongside the development of cycling prevented it from becoming a sustainable regime within Tehran’s transportation ecosystem.

Dr. Kazem Afradi, PhD in Urban Planning, is conducting the Tehran Cycling Cities project under the supervision of Professor Ruth Oldenziel at Technology University of Eindhoven. Forthcoming publication 2024.

References

Behnaz Ghafari. (2018, December 4). Hanachi cycling on “car-free Tuesdays.” Iranian Students’ News Agency (ISNA). isna.ir/xd44z6

David Herlihy. (2011). The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of an American Adventurer and His Mysterious Disappearance. Mariner Books.

Maedeh Alishahi. (2014, February 14). Old advertisements in old Iranian magazines. Sazeh Software Group (IiiWe). http://alishahi.iiiwe.com/old_advertising_in_magazines_ancient_iran_/

Mohamadreza Karimi. (2021, January 22). Celebration of Clean Air Week. Tehran Photo Agency. https://www.tehranpicture.ir/fa/album/6961

Selected photos from Qajar albums. (2019, December 20). Contemporary History Research Institute. https://www.iichs.ir/fa/gallery/8431/2

Hamshahri online newspaper. (2023, April 17). When the license became mandatory for cycling. Hamshahri Online Newspaper. hamshahrionline.ir/x8r9T