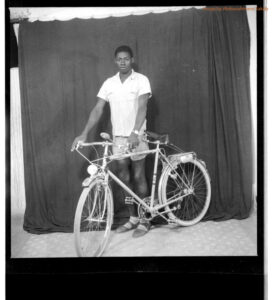

Bicycles were such an important status symbol that the people of Bamako, Mali had their portraits taken in the city’s photo studios: cyclists proudly showed off their possessions, as this 1958 image by photographer Abdourahmane Sakaly well illustrates. The earlier adopters of bicycles were European missionaries and doctors, who used them to get around for their work.

Since then Bamako, the Malian capital, flourishing on the banks of the river Niger and at the crossroads of West Africa, the Sahara, and the routes leading to North Africa and Europe, has been experienced dramatic population growth and urban sprawl since then. Once Bamako was once a compact commercial city of 100.000 (1960), guided by short distances and dominated by walking and cycling. Then many people from the countryside flocked to the city in search of work. Today over 2 million people live in the sprawling city with uncontrolled traffic increasingly ruled by motorcycles to the detriment of pedestrians and cyclists. Bicycles may not have the same status as when Sakaly created the portrait in studio in 1958. Still, many Bamako workers use the much-needed bicycle as a means of transport and as a source of income.

Based on a review of documentary research, field survey, and field observation, we analyze the factors that explain the problems that cyclists who transport goods face in Bamako’s traffic—even though they play such an important role in the local economy in filling a vital gap in the city’s transport infrastructure to meet the demand for transporting and delivering goods like vegetables, rice, corn, millet, and sugar to city residents. Today’s challenge is how to integrate the bicycle as a means of transporting goods with other modes of transport on the same traffic routes in Bamako.

Since the 1960s, public transport has failed to keep up with the spectacular growth of the city’s population. Since 1968, the Bamako government failed to keep up with the spectacular growth of the city’s population, opening the door to private businesses like Compagnie Malienne des Transports Routiers (CMTR, 1968-1976) and Société de Transports du Mali (SOTRAMA, 1978-1985), and Bamabus and Tababus between 1990s-2000. For many workers the bicycle serves as a cheap and efficient transport alternative between the place where they trade and the areas where they live. Despite their vital role, peddlers face difficulties resulting from a transport policy that ignores the Bamako’s traffic reality and fails to provide bicycle paths to protect these peddlers or solve traffic congestion.

The policy oversight is also complicated by cyclists’ social status. Many people view cyclists negatively because of their street behavior like issuing insults and parking illegally on the roads and in commercial spaces. On their part, cyclists feel unsafe on most Bamako’s roads. Faced with these difficulties, some peddlers transport their goods early in the morning between 4 am and 6 am to circumvent the dangerous traffic situation. Other cyclists avoid the vital, but busy and unsafe “Pont des Martyrs” altogether—one of the three bridges that crosses the Niger river.

Dr. Issa Fofana and Dr. Issa Togola analyze the complex story of Bamako’s cycling history in their research as part of the Cycling Cities: The African Experience made possible by The African Urban Mobilities: Past, Present and Future Network with support from the University of Witswatersrand, History Workshop, South Africa, University of College London Urban Laboratory; History Department, Bayero University, Nigeria, and Eindhoven University of Technology, TIS History Lab and SHT with support from VREF.